April 27, 2006

April 25, 2006

more questionable nomads

I drink some water, take off my sandals and walk into the ocean to be alone for three or four hours. There is nothing to see but light, nothing to feel but your body, legs and thighs and calf muscles straining at the urge to slide, energized with the new uncertainty of wether or not the ground will choose to hold you.

I feel completly alone. I can scream here. I can dream here. I can die here. I can walk for hours following the sun. But it is all an illusion. Virtually all deserts are these days. The Erg Chebbi Dunes run due north south for about 30-40 km. But they only spread about 7 km wide. They are not the Sahara or even the "doorway to the desert". They are a puddle. But they seem limitless and it makes them lovely. All this illusion, all these Berber men dressed up like Touregs, all these fake nomad camps with toilets and wells hiden by palm fronds, perfect paved roads to a desert sunset.

Much of Morocco strikes me this way. It is stunning, but never seems real. Tourism has a way of turning everything into a charicature of itself. There are always some Spanish tourists doing circles on their 4x4s over the next dune or a tourbus full of French couples snapping identical photos of a veiled woman carying water.

I talk to Brahim, a guide at the auberge for a while about life in the desert. He tells me he can take me to a "nomad" family that lives at the edge of the dunes. I ask why they would live there when there is no food for animals there. Eventually he tells me they don't have any animals, that the auberge dug a well for the family and asked them to stay there so tourists could come visit a real nomad family. It all strikes me as rather bizzare. He tells me that it is like this all over the world. That there are no real nomads left, for live from the land in the desert. We talk about India and Mongolia and Mali and he looks at me like I am full of well crafted lies.

April 24, 2006

into the desert

I leave Marrakech for the Erg Chebbi dunes outside of Merzouga with my backpack and no real hurry. I stop first to the Boudum de Dades and take a few days to hike through the gorge and spy on some shepherds. I climb up some rocks, I fall down some others, I get brought home for tea and couscous.

Then its time to move on. I check out of my auberge, buy some bread and cheese and sit on the side of the road at seven am waiting for a bus that never comes. Eventually, I start to thumb down anything that rolls by. Sadly, wealthy french tourists seem particularly petrified by hitch hikers. Evenually, all the guys on the block are flagging down trucks, vans and tour buses seeing if anyone is going to Rissani or Merzouga. Evenually a little red Fiat full of spanish kids from Madrid picks me up and the adventure begins.

It's Fete de Mouhammed and the day only gets stranger from there...

The road is good and clear and we stop once for petrol, once to visit the Todra Gorge, once for a freak hailstorm that threatens to crack the windshield, twice for sandstorms, again for directions and tajine kalia.

We stop for tea at an art deco cafe in Risani. In ten minutes we have three new friends all offering in good faith to be our guides. la shukran. la shukran. Abdoul tells David about his tent camp and tries to make him name a price for a camel trip that we're not interested in. Hassan goes on and on to me about a girl friend of his in DC that he met on the internet.

It's the Prophet's birthday and all the shops are closed and people are in the streets. Sudenly, there are shrieks and yells. Rgiht through all the sunshine and mild breeze, big fat raindrops begin to fall. The boys leap to their feet. A car skids, an old man dances in his slippers in the middle of the intersection, little children turn thier palms and mouths to the sky. Someone begins to sing. A boy crashes his bike in front of us. A policeman sits and drinks his tea slowly as his uniform changes color.

And then it's over.

I take another sip of tea. Hassan turns to me, "It hasn't rained in this town in two years". Maudé points to Delia, "It always rains wherever we go. Promise". Delia chimes in, "500 dhiram and we'll give you some more rain. Just 500 dhiram".

We drive on across an ocean of tiny black pebbles. By dusk we reach the dunes. We dust our selves off, stretch a bit and wait for the camels to take us to a tent camp. There is a lovliness about riding a camel in the dark.

Watch a slideshop of the trip by clicking here!

April 22, 2006

April 21, 2006

lost in Fez

I spend days sinkning into the beauty of the medina. I walk and walk and walk, never knowing quite where I am or where I want to get to, so perhaps I am not lost at all. I follow the hemlines of enshawled women, bags of bread being delivered, great sacks of refuse twice the width of the donkeys that carry them. For a while I follow a great pile of skins with two shaky legs. I finally pass the smelly mass and look back to see a tiny boy buried down to his chest, revealing only a sunshine yellow sweatshirt bearing the words Young and Free.

Mostly I chase after shadows and specks of light.

On my second day of wandering I become more sensitive to the sounds and smells around me. I listen to voices that I blocked out before. I allow myself to be led around; I take directions; I have conversations in my gradually loostening French. I open myself up, only half expecting someone to really hastle me, to throw a scam my way, to trap me or try something. And against Fez's reputation, no one does. I remain open, relieved. I am glad to have time again to be alone in a crowd, to let my mind skip and jump with my feet, to be without schedule, without plan, without hurry. I let the city take me into its arms. I agree to surrender. Today three strangers stopped to tell me I have a good heart. Then they walked away without even asking me to visit a shop.

I begin to meet all sorts of characters -- Missouri the singing progfessor, the grizzled 70 year old guide who lived in Harlem in the eighties and tells me all about Nancy, the kindest woman he ever loved,

the sad waiter, the cookie boy...

April 18, 2006

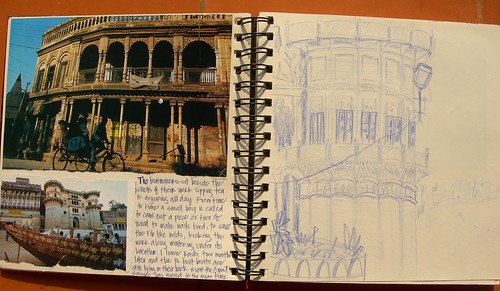

India Retrospective

“My home is with us. My village is the mobile camp. It is all my relations and friends who have left their home, and have come with their sheep. Every year my village is in a different place because there is a different group that makes up the camp… everyone changes, they become different people… ”

“My home is with us. My village is the mobile camp. It is all my relations and friends who have left their home, and have come with their sheep. Every year my village is in a different place because there is a different group that makes up the camp… everyone changes, they become different people… ”Namaste – arrival in India

Tamil Nadu – travel in the south

Leaving Benares – leaving friends and teachers for the desert

Jaisalmer Ayo! – heading out to Rajasthan to recommence the project.

Nomads in all castes and colors – brief introduction to nomadic castes in Rajasthan

Naguar Cattle and Camel Fair – a thousand men, two thousand camels and one lost white girl.

Mafkijie

Reasearch Woes and Wonder

Oh ghori, aapka gaon kahan hai? – Jaisalmer and my bhopa family

Wandering men and a very old story – Jogi part 1

We Find a Lonely Place - Jogi part 2

We Stay in this Place - Jogi part 3

Raikas

April 16, 2006

Raikas

"Our home is under the sky. our village is the forest. For 300 days out of 365 we are on the road. Using the motor road you get to your destination quickly. But we move along the narrow by-paths in the fields. Others would get lost. Instead of taking us to the end of a journey, these paths always take us to new places. Each new place is a destination. In each new place, we again sleep under the sky, our pillows. Our home is the sky. I find it wherever I go." -Kherji, a sheep herder

In the village of Sadri, twelve to fourteen hours by jeep south west of Jaisalmer, there is a woman who knows everything about camels and the desert and raikas. If you want to understand herders, go meet Illse...

I make the trek down to Pali to meet Illse and visit Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan, a local NGO that works with herders in the region looking at issues of land rights, animal health and general community initiatives for camel and sheep herders. The Raikas are fascinating and a complete shift from the musicians and performers of Jaisalmer.

Lonely men and thier animals. Opium and chai. Smoldering fires and camel milk for months on end. Endless walking. Falling wool prices and rising medicine costs. A hostile Park Services and sea of police and small scale beurocrats trying to keep the camels out of lands they have grazed for hundreds of years. Water pumped in from Punjab, farmers pumped in from Gujarat.

Vegetarian pastoral nomads who don't make use of any animal products, except for the milk of their camels. More stories of Shiva and Pabuji and the first camel and his assigned caretaker. Thirist and hunger and desperation. Dignity. Sons who refuse to follow their fathers into the hills. Girls who refuse to marry herders. Death fests and jaggery and protests with ten thousand goats in an intersection blocking a minister's car...

a Godwar Raika, drinking tea during a community meeting

a Godwar Raika, drinking tea during a community meeting

April 14, 2006

We stay in this place now-- Jogi part 3

I have spent weeks in Jaisalmer wondering when I will leave again. Then one day, I begin giving things away. I have a parcel sewn up and take it to the post office. I start looking at my pack lying in the corner of my tiny cell of a room. I wonder what I will tell Fulli. But she knows what is happening, of course. The other day we spoke of Africa. She said she was happy I would be living with other kalliwallis (black women) but that I should really come live with her in her mamma’s village where we could sing and dance and make food together.

I know that my time in Jaisalmer is over. At the end of the day, there are not any nomads here. Everyone has settled at least a decade ago. I cannot chase after ghosts. The interviews with the Jogi community were so helpful because they helped me realize that I need to move on. The memory of movement, its imprint has grown faint with these people. It’s a lifestyle they have rejected and it is clear why. There is no respect for them as Jogis. There is no more life in this wandering. Communities no longer support them and there are jobs now – honest labor, the idea of homes and land allotments and schools for their children (at some point in the future…).

So, bas. No more, says the elderly Jogi in his saffron shirt and clean white dhoti. If this ancient wandering – this restless begging was a curse from Goraknath, the casting out of Kandipath, who through his greed and deceit rendered generations of Jogis unclean – if begging is truly a daily death, then perhaps the curse has run its course and the Kalbelias and Jogis are ready to live a new life, to be reborn in a new status, to raise children with a new idea of home, to write a new story.

Homes made of mud and thatch and stones will replace beds of sand and stars. These new houses, these pucca ghar will pull these travellers away from an endless trail of footsteps, a winding road through the desert that has lead to water and grain, to a hundred faces, a hundred bowls. Dust storms already begin to erase these roads, paved with repetition, these roads that render a history and a movement visible.

The Jogis of Jaisalmer are still landless. They have no papers and for this reason are in constant fear of another eviction even though they have been living in this spot of eight or nine years. There is no school, no clinic, no market, no stability for their children. Still, they cannot settle in town. There is no place for them in Kalakar Colony. Still they find their “lonely place”. Everyday they walk the few kilometers into town or to the mines. Before we leave, Gael asks one man a question. After this long conversation about wandering and hardship and uncertainty, Gael asks, In two years time, where will you be?

Right here, Tota Ram Nath says and strikes the ground between us with his large and worn metal tipped walking stick. We stay in this place now.

I leave Jaisalmer less certain of things than when I arrived. I can still feel Fulli's kisses on my cheeks. Suman wouldn't speak to me at all on my last day. I am headed to Pali and can't say when I will be back. But still we don't say goodbye, we don't have words for that, only phir melange, we will meet again.

April 13, 2006

We find a lonely place -- Jogi part 2

Everyone wants me to understand. Old men argue amongst themselves. Imam runs in circles trying to translate between Hindi, Marwari and English. Still there are words that only the Jogis understand. I ask questions in Hindi whenever possible even though these old men don’t catch it. We stumble through four versions, hours of tape and too many questions. The story resembles all of the important things I am told while travelling – I hardly understand the words, but the meaning is clear.

The story begins with a great teacher, a guru (Goraknath) and his two disciples (Jalandernath and Kannipau). One day while travelling, the guru sends out his two disciples into the desert to collect alms for his daily meal. Who will bring me flour for making the rotis? Who will bring me dhall and namak for the subzee? Jalandernath wanders for hours with his bowl, begging a handful of lentils here, a few chillies there. The desert is full of empty stomachs and clean thalis and he has a difficult time finding anything for Goraknath. He continues to walk all day.

Kannipau meets the same difficulty. After a few hours, he comes to the hut of a farmer, or maybe it’s a banjara camp, or the cart of some Raikas, or a destitute Bhill. The site of confrontation, the object of Kannipau’s indiscretion shifts with each telling of the story. But each time, Kannipau is offered a choice. He is asked to do a service in exchange for something he can bring back for his guru. He chooses pollution in secret under the guise of duty and charity. There is always the best of intentions and always some element of altruism and self-interest. Jaldernath is a non-character, only existing as a place maker for the obedient and unchallenged. His descendants become saddhus, wandering holy men. Kannipau is cursed to remain an outcast, a beggar and a wanderer without a teacher, shroud in ignorance and poverty. He failed a test he did not know he was taking and is sent out into the desert.

Imam Deen and I are sitting at the museum with a young Jogi talking through this story and his memories of growing up the only Jogi in his dang who could read and write, who could speak Hindi with confidence. He stayed as a boarder in various small town government schools while his family wandered, sending word of where they might meet up on weekends and festival times. He wants nothing more than to see all of the Jogis settled, to built a school where he can be a teacher. All his stories and explanations carry the aftertaste of this conviction.

We cannot live in the villages; no one will give us land. It is terrible to earn food from begging.

But Diwana provides a way for all people. We have learned to live even this difficult life.

Each family wanders alone, but knows the location of other families. They organize so that they cross paths only when desired, but never visit the same homes. Groups are constantly breaking up and meeting again in other locations, setting up camp together, where there is water, but walking towards different villages to beg.

In the older days, Jogis would travel with dogs, donkeys and hens. The few possessions a family had was piled on the donkey – some cookware, a quilt, maybe a charpi to load everything on. A lucky family had some chickens riding on top of the whole lot. Jogis are famous for breeding fierce fighting dogs. They hunt with the dogs and use them for protection against hostile villagers who might try to rob them or forcibly drive them away.

We find a lonely place.

There is no space for us in the villages. So, we remain hidden.

Families moved slowly and regularly -- always on foot. I am told that for years they were prohibited from riding in trains or busses. Food is whatever is given: some left over grain, old bread, a few wilted vegetables, some tea or milk, salt, chillies. They would return at night to shelters made from a few sticks, some branches, an old disintegrating sari. Some families might fashion some sort of dera, a shelter made from odds and ends, all sorts of plastic sheets, newspaper, shrubs, glass, sticks. During monsoon, they might make a more stable hut, a jhoperi or tsupera with mud and sticks and a plastic tarp if possible. But Jogis can build homes out of anything.

There is no one solution for surviving a life of constant motion. Different Jogis find different means of feeding themselves. Sometimes the men would enter towns and offer to play music or sing, to do some pujas or work with snakes. Some say that all the folk songs of Rajasthan came from these people. For a long time Jogis were barred from traditional wage labor and rarely received any monetary compensation for their skills and wisdom. I am told most Jogis lived on begging alone.

You find beggars in all of India. What differentiate the Jogis from the many other landless people in Rajasthan are this story and this practice of movement -- this way of moving over the land and finding resources in a barren landscape.

April 12, 2006

wandering men and a very old story -- Jogi part 1

(insert yellow vest photo... )

After two months in Jaisalmer, I’m still looking for the right group of ghummakers -- for anyone who is still moving or is interested in talking about that life. I move through towns and through the colony asking my questions, looking and looking and trying to understand who these people are and what they are doing here. No matter who I ask about nomads and khanabados, eventually we speak about Jogis. Each time the conversation is so different it seems to me that every begger is a jogi and that no one could possibly be a Jogi. This term is rich.

Regardless of whatever else is said about them, Jogis are poor. Very poor and untouchable. Like other extremely low caste people in India, they seem to be talked of often, but never spoken to and hardly seen at all. Most Indians that I am “working with” at the museum and in town are surprised that I want to meet these people and to walk with them.

Here is what I am told about Jogis from various residents of Jaisalmer:

They are beggars.

They are dirty and uneducated.

They are lazy and refuse to work.

They are snake charmers.

They are musicians and dancers.

They can’t play any instruments and hardly dance.

Their women dance in public and are prostitutes.

They are holy men and ascetics.

They are cheats and will steal all my money.

They are very holy and live off alms alone.

They have hunt with fierce dogs and are very dangerous.

They eat meat and are unclean.

They only eat three day old rotis that dogs won’t touch.

They are Kalbelias.

They won’t talk to me.

They are not very interesting.

They live on the street.

They live in the desert.

They don’t live here.They don’t exist anymore.

They They have to beg for land to bury their dead.

When I start asking too many questions of Imam, my default expert, he completely uncharacteristically says that he doesn’t know anything about them. I’m shocked. For weeks Imam has had an answer and a story for everything. Two days later we start interviewing Jogis together. But it’s a difficult business.

I am still hung up on this question of why? Why did these people become wanderers? Why did they keep this lifestyle for hundreds of years, through periods of massive change in India and why are they giving it up now? What has changed?

For the jogis, it all comes back to a very old story. Like all great origin stories, it is one that everyone in the community knows and that everyone tells differently. So when ten elders and three outsiders get together in a room it is a very confusing affair. It is not a folktale, but a bahut purana bhat (a very old story). We struggle together through the telling and retelling because they want me to understand it.

April 10, 2006

Oh Ghori, aapka gaon kahan hai? ... Mei Kalakar Colony mai, meri bhopa bhahen ki sat raheti hung. Aur aap?

I live in Kalakar Colony with my bhopa sister. And you?)

All together I stayed in Jaisalmer for nearly six weeks. They were weeks filled with frustration, intense learning, a bit of lonliness and quite a lot of love. All of the love came from Fulli. For one month, I visited Fulli every day. We bought groceries and cooked together. We took tea together. We ate together. We sang together. Fulli taught me, more than anyone else, how the Kalakar Colony functioned, and how the musicans and artists had made a home for themselves. With an amazing heart, a good deal of patience and remarkable openness, Fulli brought me into their community. She claimed me as her ghora and made me her sister.

Me posing with Fulli, Suman and Pinky

Almost every night, I would sigh loudly, shift SUman's sleeping body in my lap and say, Ha ley, Fulli, mei jah rahi hung. She would grab my arm and say, "Sapana, my sister, you are coming tomorrow, right?"

I met Fulli along with the other Bhopa women, sitting in rows at the entrance to the Jaisalmer fort trying to sell imitation silver bangles to tourists. Sometimes they would sing. Other times they would just sit and drink tea. Business was bad. No one ever bought their bracelets.

After listening to her call out to me two days in a row, one afternoon I stopped to talk and bought everyone tea. Somehow Fulli pursuaded me to stay for three hours. Somehow she pursuaded me to come home with her to have tea and listen to her sing with her husband. It seemed harmless enough.

After three days we were eating off the same thali and taking care of her children together. Fulli cooked the subzee and I made the rotis. She would send her husband off to spend time with his friends playing drums or ravanta so that we could be alone. On the few nights when I made other plans and told Fulli that I wouldn't be coming to see her, she declared, If you don't eat, then I don't eat. No eating in a hotel for my sister!

And she meant it.

We were two little girls playing dress-up. It became very important to her that I stop wearing my salwar kameez and khurtas and start wearing bhopa clothing. My lack of jewlery upset her greatly. Fulli had nothing but was constantly giving me things. At first I thought these were all just ways for us to play together, for me to give her money in exchange for something (for sewing me two full sets of clothing and making me jewelery) , for her to teach me a skill (she was the only bhopa girl in the colony who could do the traditional beadwork). But the money only upset her. I bought boxes of ghee and sweets and fruit instead. And if she saw me out of my Bhopa clothing, she would get very upset and sulk terribly. It took me a while to realize that she was actually making me family. She was teaching me how bhopas treat their sisters -- with gift giving, communal cooking, childcare, physical affection. In fact, she didn't have new clothes made for me, but re-sewed her own worn clothing so they would fit my considerably larger frame. Just as her older sister, Rampatti had done for her.

Me, with my hands in the dough. Suman with the ghee pot on her head.

Me, with my hands in the dough. Suman with the ghee pot on her head.

Everyone in town had something to say when they saw us together. Fulli and I would walk side by side through the market street back to the Colony. Suman would cry or pout if I didn't hold her hand. I learned to ignore all the questions and rude comments. Oh, you can't eat with those people... and Do you really drink the water? and You know, they only want your money. You shoudn't trust those women...

I learned to bury my skepticism. All my critical views on power dynamics and hierarchy and manipulation and just open my heart. It is not the worst sin to love too much or too freely. For the first time in my life, babies were falling asleep in my arms and I gained another sister. Fulli and I would laugh all the time -- at the kids, at the crazy colony dogs scavenging for food, at the rats (my special friends), at oursleves. My evenings passed quickly and it bacame hard to make plans to leave. but surely enough, as interviews dragged on, I began glancing at my backpack and giving things away again. Fulli knew what was happening and began to call me on my mobile from payphones during the day to ask where I was and make sure i was coming for dinner. We talked a bit about Africa. And Fulli said once, only mostly joking, okay, you take Suman with you. Another night she asked me, In Africa, everyone is black like me, no? Maybe you will become a kalliwalli. That would be very good. You find yourselve a dark man.

Don't worry, Fulli, if I ever find a man to marry, I bring him to meet you first. If he can live in the Colony; if he can learn to play Ravanta and sing Pabuji; if my sisters like him; only then will we get married. I say this in jest and realize its actually quite a good idea. That such a person would be impossible to find.

Pinky (Niccola) getting into the lentils

Pinky (Niccola) getting into the lentils

April 08, 2006

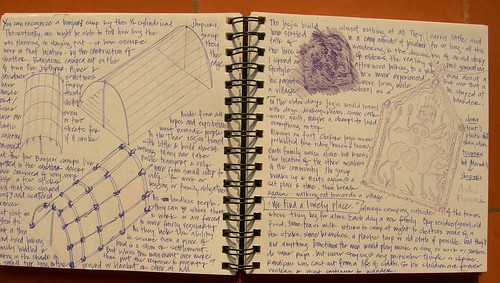

Research woes and wonder

''It is only after you have come to know the surface of things, that you can venture to seek what is underneath. But the surface of things is inexhaustible.'' Italo Calvino, speaking of the pigeons and their view of the city in Mr. Palomar.

I remind myself again and again that I am not on the Great Nomad Hunt, running around the desert looking for some mythical, sufficiently exotic peoples. I am thirty years too late for that. Its not possible with my comfortable,relativist, post-colonial, post-modern, subaltern, anti-authoritarian leanings and my own little Edward Said whispering sweet nothings in my ear.

So, yes, I am trying to learn about nomadic people, about their way of life, about that intransient nomadic ethos in a place where the nomads have all but disappeared. But I am also grateful just to talk about ideas of nomadism, to understand how modern Indians think and talk about Jogis and ghummakers; how communities write stories about each other, write and sing each other´s histories for better or worse, fact or fiction. There certainly is a lot of fiction.

History may be in the details, but it is the stories which move us. Again, I find myself a collector of stories. There is no fact checking in storytelling. Merely listening, filtering, contextualizing. All of these words are loaded. There is no truth, only references. Each comment contains its own truth. Even the most complete lie serves a purpose, fulfills an intent, betrays a motivation to conceal, to mislead, to sway. I am exhausting myself with an inexpressible number of whys and hows. So, I content myself for a while not with order or meaning, but with narrative.

I grow fat with chai and discourse.

I spend my dazs doing interviews, driving around the desert visiting villages with Jathu Singh on his motorbike, and my evenings with Fulli and my bhopa friends, making roti and subzee and playing with the kids. I wonder if I still expect any great insight and I wonder how this ´project` will come together. I struggle to find coherence in these great leaps in space, time and culture. The more time I spend in India, the more I learn and the less I understand. I feel like I have nothing but fractured knowlege, made almost entirely of exceptions, particularities and contradictions.

How can I make generalizations out of all these faces and stories and lives when I feel that it is impossible and pointless to do so? How to convey these teachings, the wisdom these people have so generously shared with me?

I hold in my hands a mess of notes, sketches and poorly composed snapshots - portraits with blurred backgrounds and captions written in scripts I can hardly pronounce.

April 03, 2006

mafkijie

Mangiyar musicians playing at the Sam sand dunes

Rajasthan tossed me around a bit, but also gave me some beautiful moment and important lessons. I quest to learn more about nomadic life and issues of movement led me to many small village throughout the Jaisalmer district, cattle and camel fair in Naguar, a small town in Pali and the pilgrimage and tourist oasis of Pushkar. All and all, my time with the ghummakers and Raikas has been well spent and was a fascinating experience, even if I emerged with far more questions than answers.

Promise i'll get at least two more rajasthan posts up in the next week along with a recap and some notes from Kerala. its all in the notebooks...

In the meantime, I have uploaded lot of new photos onto my flickr site.

click here for camels, gypsies, deserts, houseboats and the ocean.